In 2014, I wrote my first experimental book review and I’ve since written seven more, with plans to write as many as I can so long as people keep finding them interesting. Each one is a puzzle to write but I like what they allow me to do, as a form, compared to more traditional criticism. They’re written in third person about a critic, rather than as a critic. Each piece can stand alone, but if they are read sequentially, they show time passing for the critic, and her family, as her career goes on.

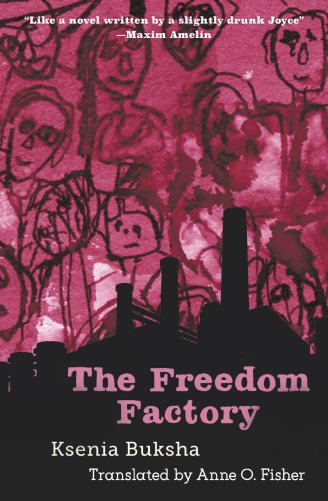

The latest review is about Russian author Ksenia Buksha’s novel, “Freedom Factory.” It was published this spring in the online cultural journal, The Critical Flame. Here’s an excerpt, with a link to the full piece below.

The next one will appear this summer in Textshop Experiments. It’s focused on “Aviaries,” a novel by the late Czech author Zuzana Brabcová.

Party On: An experimental review of Freedom Factory

The critic had missed her deadline and couldn’t bring herself to care.

On her couch, with her laptop on the coffee table, she looked at her notes about the book and read a quote: “The factory is a continuation of my father.” Ksenia Buksha had placed it near the end of her book, in one of the more experimental chapters. It had been meant, the critic thought, to convey a sense of something spiritual about the way the place a person works can enter their lifeblood.

The critic had stopped reading when she’d seen this sentence. When she started reading again she saw that she’d misread “factory” as “family.” Perhaps families are a sort of factory, she wrote in the margin. A tiny town of souls with fates and gossip.

As for her deadline, life would go on for her and her editor, and the book’s author and publisher, whether or not her review ever appeared.

At her mother’s sixty-fifth birthday party that weekend, she felt like she was near the center of her tiny town’s gossip. It started when her sister walked over to say she’d noticed their mother was drinking less than usual. “It’s that church guy,” her sister whispered. The critic nodded and looked at man, realizing she might have been glaring.

“That church guy” was a widower, a former high school Spanish teacher with three grown children. Their mother had known him before their father died. He’d urged their mother to start going to mass and she had gone, because he’d asked in just the right way. All he had said was, It’d be nice to see her there. No guilt-trip. Just a friendly comment. It would be nice to see you.

The critic thought of the washer in Buksha’s book. There was a wonderful scene—one of dozens superbly translated by Anne Fisher—where two Russian manufacturing engineers are about to test a submarine they helped build. But the electrical system isn’t responding. Nothing, no power. So one of them opens a control panel, crams in a washer wrapped in duct tape, and tries again. Just like that, it’s all systems go. One tiny washer, or the right comment well-delivered, and things come to life.

A few people at the party glanced in the critic’s direction, then toward her mother, who was talking to the church man. A new phase was beginning for their family, one that would, on some level, move her late father further back into the past. It would be a very different sort of relationship for her mother with this man. A new love late in life. No pressure to start a family, and they’d have lots of time for themselves, since they were both retired.

The church man seemed okay. He drank light beer, rather slowly. This was a relief with strange contours: the critic cared, in a specific way. He wasn’t Mr. Piety, but he wasn’t a lush—a fairly tall order for a lot of men in the Midwest. Her mother looked happy, and not the drunken barely-happy of the last few years.

The critic gulped at her wine as she watched her mother smile at this man. Family, she thought. Just when you thought certain things were settled, people swerved. Producing more gloom or joy or silence or love. Giving up pieces of their freedom to chase new dreams.

The Freedom Factory that Buksha wrote about was a real manufacturing facility in Leningrad. It opened in 1928 with “a brigade of young shockworkers…the precursor of our communist labor brigades.” A secret, military factory, it produced missiles, submarines, and other equipment for war. Buksha omitted hard dates, but the book seemed to cover from about 1960 to the mid-1990s, slightly beyond the dissolution of the U.S.S.R.

It was a surprisingly hilarious novel, a bubbling pot of big personalities, forty short chapters bursting with historical detail, wit, conflict, and a solid balance of Communist Party nostalgia with bitterness about Soviet hardships.

Buksha showed life up close for the workers. Their pride and struggles, specialized skills, and dreams of escape amid the collective success. Fisher brilliantly adjusts her translation to follow the many modes Buksha’s prose adopts. And it’s no simple task. Buksha’s a poet, equally adept at dialogue-heavy, realist, oral history as she is at creating lush, literary character portraits, in an array of settings from the factory floor to a ship bound for Cuba.

The characters have one-letter names or first names only (Valya, Tanechka, Verka, Pashka) as if Buksha is protecting their identities while also stamping them as stock characters in a socialist narrative about the glory and folly of labor conditions under Soviet rule. Glimpses of their faces seem to appear in some of the author’s abstract, black-and-white illustrations.

In the book’s more stylized passages—sometimes mixing dialogue with exposition, omitting quotation marks, dialogue tags, and line breaks—the critic had to parse the text quite carefully in order to follow along. Buksha, she understood, didn’t do this for mere effect. She made meaningful, often touching, points to end almost every chapter, to capture the tone and spirit of the people over several decades in this place.

The critic watched her sister introduce her four-year-old daughter to the church man. Standing nearby, her mother put her drink down, then picked it back up. The moment had caught her off guard, perhaps. Then she crouched down to help smooth this introduction to her granddaughter.

This is a moment our family has built, the critic thought. A tableau at a family event. If she wrote fiction she wasn’t sure how she’d describe it. Buksha had the knack. She could see beauty in the workers’ pride as they built data link targeting systems for Yak-28L tactical bombers. She could draw empathy for young men like F., who’d rather be sent to Antarctica than work a single day at the factory. The scales of pride and loyalty versus disgust and corruption. That rang true. Given the choice, who wouldn’t be reluctant to commit to a lifetime of unknown work with a bunch of strangers?

Here is the full review at The Critical Flame. Thanks for reading!

I am waiting until she gets all meta-fictional on you and writes a review of a book by Matt Jakubowski.

LikeLiked by 1 person

She’d do that. Just biding her time, I think.

LikeLiked by 1 person